Category Archives: A Frussian Diary

17 years in Russia

Today is a special day, a day that resonates deeply with me.

Exactly 17 years ago I arrived in Russia, a country that over the years has become not just a place to live for me, but a real home.

I remember that Lufthansa flight to Moscow, my arrival at Sheremetyevo airport covered in snow, the first night in my first apartment in Perovo – the beginning of a new life.

A life that turned out to be rich, intense and deeply transformative.

17 years in Russia.

Russia is a country where people live with a capital letter. Each of the more than 6,200 days spent here was an adventure, a discovery, an emotion.

There was not a single gray moment, not a single similar day, not a minute of boredom.

Each day was unique, permeated with that special energy that fills this country.

Here I was able to achieve what I could not even dream of in France.

I met amazing people, people I probably would never have crossed paths with anywhere but Moscow.

These encounters shaped me, opened up unexpected horizons for me, and restored my faith in Homo Sapiens.

Over the course of 17 years, I started a family. I became a husband, a father, an entrepreneur.

I learned to live in a country with amazing political stability and, at the same time, fascinating unpredictability.

Russia taught me to feel all the ups and downs of life, to accept the ups and overcome the downs.

In 2022, for the first time, I experienced deep fear for Russia – perhaps even more than for myself and my family.

And then I learned to live in a country subjected to the most extensive sanctions in the world, to adapt, to find solutions, to get around obstacles.

One after another.

And then I decided to go against the tide. I created Ruspatriation – a unique project that did not exist before me. A project that embodies my love for this country and my desire to contribute to its future.

An anthropological project.

In 2024, a new chapter began with the emergence of “Welcome To Russia”

Russia has changed me deeply and for the better.

My move here was not just a one-way emigration.

It was my second birth.

Come To Russia !

Follow the advices from MARIA BUTINA 🙂

Chaîne du frussien : Comment s’intégrer et socialiser en arrivant en Russie ?

TIME TO MOVE TO RUSSIA

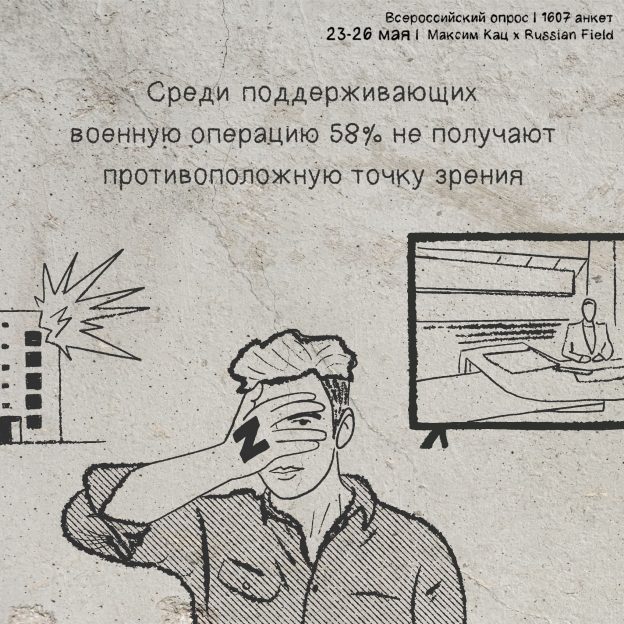

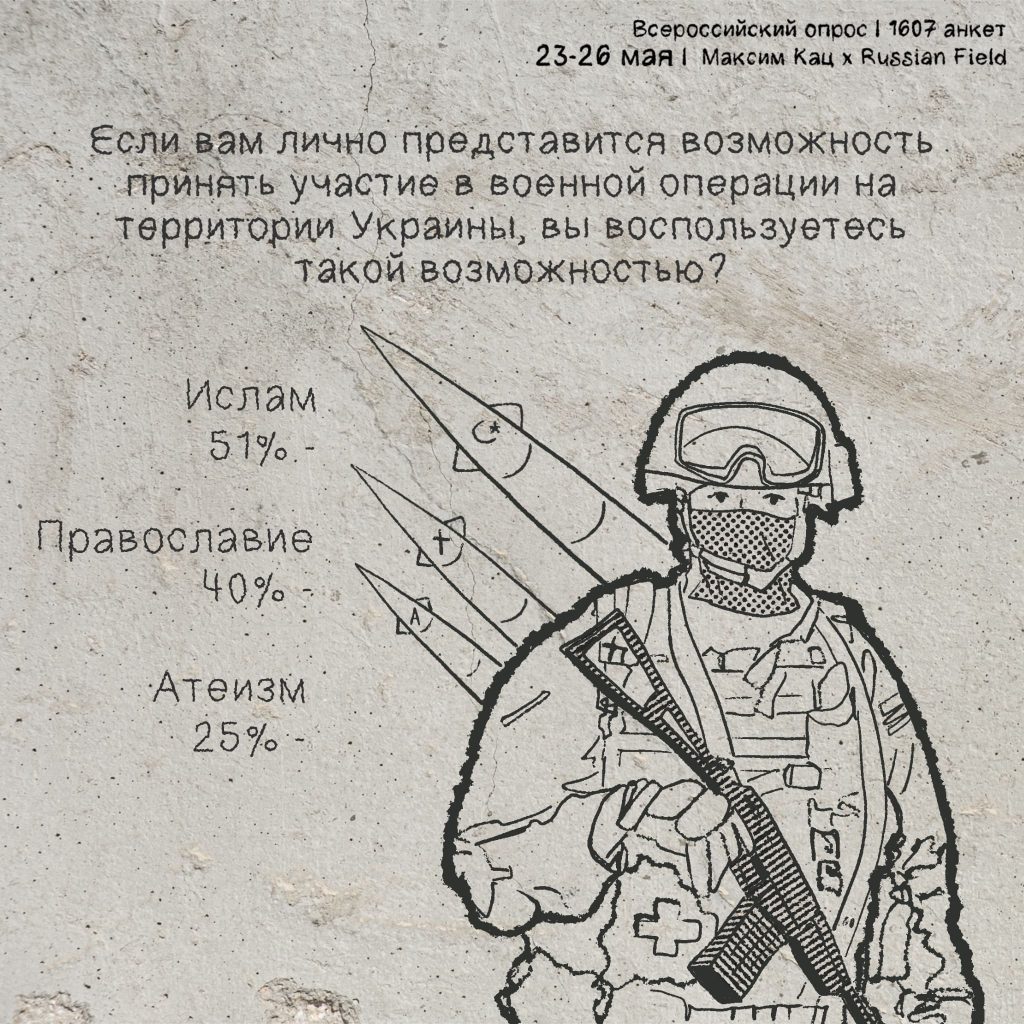

Soutien à “l’opération spéciale” et religion en Russie

Le blogueur Kireev a publié un sondage concernant le soutien à “l’opération spéciale” en Ukraine en relation avec le statut religieux, qui s’est tenu du 23 au 26 mai 2022.

52% du total des sondés de 18-29 soutiennent l’opération spéciale.

65% du total des sondés de 30-44 soutiennent l’opération spéciale.

71% du total des sondés de 45-59 soutiennent l’opération spéciale.

80% du total des sondés de 60+ ans soutiennent l’opération spéciale.

Chez les orthodoxes

74,5% soutiennent l’opération spéciale et 18% ne la soutiennent pas

Chez les musulmans

53% soutiennent l’opération spéciale et 29% ne la soutiennent pas

Chez les Athéistes / Agnostiques / Autres religions

46% soutiennent l’opération spéciale et 43% ne la soutiennent pas

51% des musulmans sondés considéreraient de participer à “l’opération spéciale”.

40% des orthodoxes sondés considéreraient de participer à “l’opération spéciale”.

25% des athéistes considéreraient de participer à “l’opération spéciale”

En moyenne 37% des sondés considéreraient de participer à “l’opération spéciale” et 37% des sondés ne considéreraient pas de participer à “l’opération spéciale”.

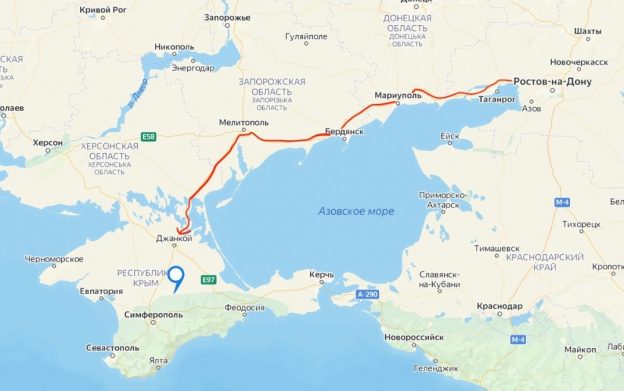

La route Rostov-sur-le-Don – Marioupol – Melitopol – Crimée est ouverte

Le ministre russe de la défense russe vient aujourd’hui mardi 07 juin d’annoncer que la route terrestre permettant de relier le territoire de la Russie à la Crimée par le continent était ouverte.

En outre, le ministère de la Défense et les Chemins de fer russes ont repris le trafic ferroviaire à part entière entre la Russie, le Donbass et la Crimée sur six tronçons ferroviaires.

A response to Arnold Schwarzenegger / Ответ Арнольду Шварценеггеру

Ue sportive russe répond a Arnold Schwarzenegger suite a son message au peuple russe.

Pour écouter la réponse de Maryana Naumova, cliquer ici

*

Suivez moi sur Telegram pour recevoir des informations / photos de ce qui se passe en Russie : https://t.me/alexandrefrussien

I live in a zero-covid world

Ci-dessous un article de The Economist que l’on aurait pu intituler :

Why China will win.

The most important page in my passport is creased from being examined so often. Thankfully, the red-ink stamp in one corner, marking my last entry into China, is still crisp and clear. I know the date by heart, after volunteering it to railway inspectors in white protective suits, to hotel clerks and airport guards and police officers at highway checkpoints, dozens of times over the past 22 months.

For many Chinese, outside the largest cities at least, a Westerner has been a rare and troubling sight since this country all but sealed its international borders in March 2020, soon after the covid-19 pandemic began. In a worst-case scenario, I might be a recent, virus-laden arrival from an outside world that – as China’s propaganda machine never tires of relating – stands for government dysfunction, individual selfishness and death.

“I live in Beijing. I’ve not left China since before the pandemic,” I call out, my passport already open at the right page. “I’ve had the Chinese vaccine. Here’s my last entry date. See here: January 21st 2020.”

Even this information is not always reassuring. To be a foreigner in this jumpy, closed-off country is not dangerous – I have faced no overt aggression during the pandemic. But it is unsettling. I’ve had Chinese passengers refuse to sit next to me on domestic flights, and watched an appalled parent yank a small child back out of a lift, after spotting me inside.

To be ill in zero-covid China has become a form of deviancy

Ordinary Chinese have a horror of catching covid that is sometimes hard for outsiders to grasp. Here in Beijing, it would require exceptionally bad luck to get the virus. At the time of writing, this city of 22m people has found a total of just 13 cases in the past month. That is not for lack of searching: residents must undergo many temperature checks each day, and submit to contact-tracing systems that oblige them to scan a QR code with their smartphones each time they enter a public building or take a taxi.

Nor is it likely that the capital is simply hiding mass infections. For sure, China’s secretive, one-party regime is quite capable of lying. Officials in the central city of Wuhan covered up their discovery of a new coronavirus for weeks in late 2019 and early 2020, silencing doctors and ordering virus samples destroyed. To this day, government mouthpieces promote conspiracy theories that the virus began in an American military laboratory, or entered China on frozen food from Europe: any hypothesis will do, if it deflects attention from that first detected outbreak in Wuhan.

But China is an autocracy guided by cold self-interest. And concealing large numbers of cases now would sabotage surveillance systems built not just to manage the spread of the virus, but to eradicate it. It has even less interest in allowing sickness to grip Beijing, the heavily guarded home of top leaders and host city of the Winter Olympics in February.

Logic suggests, therefore, that Beijing is indeed close to covid-free, as officials claim.

Even so, in this safest of cities, most pedestrians and cyclists wear face-masks of their own accord, and mask-wearing is strictly enforced on buses, metro trains or in shops. That fear of covid is partly medical, for official media have played up the dangers of the virus. But shame plays a large role, too.

The price of reporting on this giant experiment, first-hand, is staying inside a China-sized bubble

A Beijinger with covid faces social stigma. A single infected individual is enough to see entire housing compounds locked down for 14 days and workplaces quarantined, triggering the loathing of neighbours and colleagues. The children of the sick are schoolyard pariahs. If that weren’t pressure enough, local officials in provincial cities including Chengdu, Harbin, Wuxi and Shangrao have entered the homes of quarantined residents and killed their pet cats and dogs, citing the risk that animals might transmit the disease.

To be ill in zero-covid China has become a form of deviancy.

Beijing residents who develop a temperature above 37.3°C, for any reason – including as a side-effect of having a covid vaccination – are supposed to report to a fever clinic to have their blood drawn and screened for antibodies, their chests scanned, and nose and throat swabs taken for nucleic-acid tests. Self-treatment can lead to arrest, if someone with a high temperature is later found to be positive for the virus. Two pharmacies in suburban Beijing lost their licences after selling fever-reducing medicines to a couple without logging their names in a virus-tracking database.

Non-essential travel is an anti-social act.

My passport, with its precious pre-pandemic entry stamp, has helped me make reporting trips even during mini-surges in infections.

Now, with the Omicron and Delta variants beating at China’s doors, the rules have tightened again. Currently, if I leave Beijing I may return only if I can show a negative nucleic-acid test taken within 48 hours, a green Beijing health code on my smartphone (certifying that I have not been flagged as sick, nor been near a suspected case in the past 14 days) and a blemish-free travel history.

That history is displayed on a separate smartphone app that uses mobile-phone signals to trace my movements.

A trip to a county or city district with even a single case of covid in the past fortnight triggers a Beijing entry ban. Visiting any of the 51 Chinese counties that lie on a land border is also grounds for exclusion from the capital.

A police state sees opportunity as well as a challenge in these travel curbs. Since the start of the pandemic, police and local propaganda officials have routinely forced foreign journalists to cut short reporting trips to sensitive areas by threatening to quarantine them on the spot for 14 days or more. This has happened to me in Hunan, Henan and Jilin provinces. In Xinjiang in western China, an already intense surveillance apparatus has added covid tests to its arsenal of controls. On my most recent visit to that unhappy region, I had the striking experience of hearing all passengers in a packed train ordered to stay in their seats as we pulled into Urumqi station. Officers in white hazmat suits then marched the length of the train to find the foreign passenger on board, and pull me off for questioning about when I last entered the country – and also, oddly, whether I like China or not.

The fear of covid is partly medical, but shame plays a large role, too: a Beijinger with covid faces social stigma

There is still less tolerance for travel outside the Chinese mainland. To prevent imported infections, authorities have capped international passenger flights at 2.2% of pre-pandemic levels, stopped issuing tourist visas and largely stopped the delivery of new passports to Chinese citizens.

My date stamp from January 2020 records an overnight trip to Hong Kong to attend a conference. Were I to attempt the same journey today, it would be a more than month-long commitment, involving multiple covid tests, a week of compulsory quarantine in Hong Kong, two weeks of quarantine in a government-approved hotel on returning to Beijing, a further week of home quarantine then another week reporting my temperature to officials in my local neighbourhood.

The last time I travelled overseas was in December 2019, when I flew twice to London in the same month. Leaving aside jetlag and the impact of my carbon footprint, this was relatively painless, thanks to a multiple-entry visa. Covid changed all that. Foreign journalists living in China saw the border-crossing rights of their visas cancelled in late March 2020. They were restored only in May 2021, months after business travellers were once more allowed to come and go.

The British government’s insouciant approach to covid has left the country on China’s high-risk list. With no direct flights between Britain and China, arriving in Beijing from London requires a transit through Frankfurt, Paris or some other third city, where a battery of covid tests must be submitted to the local Chinese embassy or consulate for approval. With Beijing essentially closed to international flights, arrivals are diverted to provincial cities, where passengers must quarantine for 21 days before heading to the Chinese capital. Anyone who tests positive for covid or shows a fever on arrival will be hauled off to a government clinic and released only after multiple negative tests. Children and parents travelling together are separated if one of them tests positive.

This strictness has costs. It is not hard to meet foreigners living in Beijing who have gone for more than 18 months without seeing spouses and university-age children. I am one of them. Many more Chinese families have suffered. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese students have been trapped overseas by travel curbs, for instance. Many foreigners are about to spend a second Christmas in China away from their families. But still more Chinese will spend the upcoming Spring Festival holiday in Beijing, unable to travel home to their village for a third year in a row.

It would be wrong to obsess over foreign-travel rights in a country where 87% of citizens lack passports. China is not about to ease its zero-covid policies, and there is no clamour from the public for such a change. In a large country with a relatively weak health-care system, an American-style approach to the virus could quickly overwhelm hospitals.

It would help if China approved foreign mRNA vaccines like Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, which are far more effective than local versions that use an older technology. But that would involve a political loss of face. Instead, China’s ruling Communist Party touts its strict handling of covid as a mark of good governance, while scorning Western democracies for their decadence.

In consequence, the country will stay closed for a long time, or at least until more potent vaccines and anti-viral drugs are widely available. The price of reporting on this giant experiment, first-hand, is staying inside a China-sized bubble. I will be using that old date stamp for a while. ■

David Rennie is The Economist’s Beijing bureau chief and Chaguan columnist

ILLUSTRATIONS: NOMA BAR

In Bio Veritas

J’ai déjà évoqué sur ce blog le projet de système biométrique unifié (projet de la banque centrale et du provider de communications Rostelecom visant à la collecte des informations biométriques et à les utiliser pour identifier (à des fins d’authentification) les utilisateurs de services principalement financiers.

La Douma russe examine un projet de loi dans lequel, en deuxième lecture, des amendements sont apparus sur la possibilité de soumettre des données au système biométrique unifié (EBS) de manière indépendante via une application sur un smartphone.

L’objectif premier est de permettre que le visage et la voix deviennent un moyen de d’identifier et ainsi permette aux utilisateurs d’avoir accès à une gamme de services numériques dans les agences gouvernementales et les banques.

L’objectif est surtout aussi de vulgariser le service auprès des citoyens, en les encourageant à terme à passer à la biométrie à part entière.